Cross-platform MVVM with ReactiveUI and Xamarin

Usually the development projects I work on in my own time are quite different to the sorts of things I do in my day job - just to broaden my knowledge a bit.[1] It sometimes happens though that, once you start thinking about how you’re going to implement something, you begin to wonder if .NET isn’t really the best tool for the job anyway! Well, if that happens, don’t dismiss it too quickly. It could actually be a viable option - even if you’re working on some non-Microsoft platforms…

In this post I’m going to describe how I took the View Model and non-UI code from a simple desktop WPF application and re-used the code in an Android application built with Xamarin.

A bit about the application

TurboTrainer is a really simple application that loads in a GPX file and plays it back in real time, displaying the route’s current gradient on the screen.[2] I did say it was simple…

The main thing that makes .NET a good fit is that the ‘replaying’ of the GPX route, updating the displayed gradient at the appropriate time intervals, becomes fairly simple using Rx’s Observable.Generate…

var firstSection = sections.FirstOrDefault();

if (firstSection == null)

{

return Observable.Empty<GpxSection>();

}

var sectionsEnumerator = sections.Skip(1)

.Concat(new GpxSection[] { null })

.GetEnumerator();

return Observable.Generate(initialState: firstSection.TimeTaken,

condition: x => sectionsEnumerator.MoveNext(),

iterate: x => sectionsEnumerator.Current == null ?

TimeSpan.Zero :

sectionsEnumerator.Current.TimeTaken,

resultSelector: x => sectionsEnumerator.Current,

timeSelector: x => x,

scheduler: scheduler)

.StartWith(firstSection);And (probably more impressively), even though the above code is all about scheduling and timing, it can still be unit tested by using the time-bending magic of the TestScheduler. (Have a look at these unit tests in TurboTrainer’s GitHub repository to see some examples of using the TestScheduler to test this code.)

As well as the above code, the project also includes…

- auto generated code[3] for the XML deserialisation of the GPX files

- code for calculating the distance and gradient between two GPX points

- a ReactiveUI view model …unit tested, of course!

- a WPF window with the bindings to the view model set up in the mark up, and very little in the code-behind.

Fair enough. A pretty typical WPF application.

But if you’re using the app, you might not want to use your desktop or laptop. A mobile app might be more convenient. And, of course, if we’re going to write a mobile app, we’re not going to narrow our user-base to only those with a certain type of device. But porting all of that code to each of the native platforms sounds like far too much hard work!

Well, Xamarin claims that you can ‘write your apps entirely in C#, sharing the same code on iOS, Android, Windows and Mac’. And, because I implemented my view model with ReactiveUI (which now has support for Android and iOS Xamarin applications) I should be able to re-use the view model also. In other words, pretty much everything apart from the UI itself could be shared between the platforms!

To put it to the test, let’s see if I can take all of that code (apart from the WPF window) and use it in a Xamarin Android application…

Creating an Android ReactiveUI project in Xamarin

To create the basic skeleton of the project and get all the assemblies you need…

- Create a new solution using the Android Application template.

- Add the Reactive Extensions component from the component store. (Find out how.)

- Grab the

ReactiveUIandReactiveUI.Androidassemblies from the starter-mobile project and reference them in your project. (They’re in this folder.)

If you prefer, you could just skip this and start with a clone of the starter-mobile project as described here. I find, when I’m trying out new stuff like this, that I get a better understanding of what’s going on if I build things up from scratch myself…it’s up to you.

Next, we need to find a way of sharing the code between the WPF application and the Xamarin Android application. There are a few ways to do this, including building the shared code into a Portable Class Library (PCL). For this small project I went with straight-forward file-linking. I liked the convenience of being able to edit the shared code in whichever project I was currently working on and for it to be ‘magically’ updated in the other. But this also makes it quite easy to make some changes in one project which cause compiler errors in the other so I could see this approach becoming unwieldy in a bigger project. Another drawback of the file-sharing approach is that if you add or delete files in the shared folder you have to do it in both places. Again, it’s up to you!

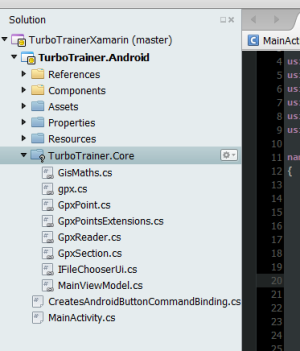

The TurboTrainer.Core folder doesn’t really exist - it links to the shared files in the WPF application.

Finally, we need to make some changes to the MainActivity to get it ready for MVVM and the ReactiveUI framework. Make it implement IViewFor<MainViewModel> and derive from ReactiveActivity instead of a plain Activity…

public class MainActivity : ReactiveActivity, IViewFor<MainViewModel>

{

#region IViewFor implementation

public MainViewModel ViewModel { get; set; }

object IViewFor.ViewModel

{

get { return ViewModel; }

set { ViewModel = (MainViewModel)value; }

}

#endregion

...ReactiveUI Bindings

If, like me, you’ve only ever used ReactiveUI in a WPF application then you might not have realised that it has its own bindings. Here’s a very quick overview of ReactiveUI bindings, (you can find out more from Paul Betts’ NDC 2013 talk)…

This creates a 2-way binding:

this.Bind(ViewModel, vm => vm.Username, view => view.Username.Text);Here’s a one-way binding (from the View Model to the View):

this.OneWayBind(ViewModel, vm => vm.ShouldShowSpinner,

view => view.Spinner.Visibility);This also illustrates a built-in converter (binding from a bool to a System.Windows.Visibility). You can extend the built-in ones by registering your own custom converters.

Here’s an example of binding to a command:

this.BindCommand(ViewModel, vm => vm.DoLogin, view => view.LoginButton)There are a series of classes that know how to make command bindings (for example, by looking for a Command and CommandParameter property, or, by looking for a Click handler). The framework looks at the view property passed in (LoginButton in the above example) and chooses the one most appropriate for that type. (Again, you can extend these by registering your own. There’ll be a bit more about this later!)

Of course, in a WPF application it’s easier just to define your bindings in the XAML mark up and let the WPF binding framework do its job. There are still plenty of benefits to using ReactiveUI with the WPF binding framework, though. For example, you get less verbose notifying properties…

public GpxSection CurrentSection

{

get { return currentSection; }

set { this.RaiseAndSetIfChanged(ref currentSection, value); }

}…and the benefit of being able to compose your property update handling…

this.WhenAny(x => x.ViewModel.CurrentSection, x => x.Value)

.Where(x => x != null)

.Buffer(TimeSpan.FromSeconds(3))

.Where(x => x.Count != 0)

.Select(x => new GpxSection(x.First().Start, x.Last().End))

.ObserveOnDispatcher()

.Subscribe(x => gradientText.Text = string.Format("{0:0.0}%", x.Gradient));…and probably a few other benefits that I won’t go into here.

In our Android app we have to rely on ReactiveUI to provide the bindings. Set the ViewModel and then set up the bindings in the OnCreate of the MainActivity…

ViewModel = new MainViewModel(RxApp.TaskpoolScheduler, this);

GradientText = FindViewById<TextView>(Resource.Id.gradientText);

this.OneWayBind(ViewModel, vm => vm.CurrentSection.Gradient, v => v.GradientText.Text,

x => string.Format("{0:0.0}%", x));

LoadGpxButton = FindViewById<Button>(Resource.Id.loadGpxButton);

this.BindCommand(ViewModel, vm => vm.LoadGpxDataCommand, v => v.LoadGpxButton);Notice that this means naming our controls in the UI mark up and looking them up by their id in code. Maybe a little more effort than just defining the binding directly in the UI mark up but I’m pretty sure it’s a lot slicker than trying to do it in a non-MVVM way.

Scheduling and the ObservableAsPropertyHelper

The first time I plugged the View Model into the Android application it crashed with a CalledFromTheWrongThread exception. It’s the old ‘you’re trying to update the UI from a different thread, you idiot’ error…such a rooky mistake! How embarrassing. Really, I should know better!

But, wait a minute…WPF has the same kind of thread affinity requirements. Why didn’t I see the problem in the WPF version? Well, it turns out we’ve been spoilt in the WPF world. In WPF, suppose you have a notifying property…

public GPxSection CurrentSection

{

get { return currentSection; }

set { this.RaiseAndSetIfChanged(ref currentSection, value); }

}…bound to a text block using the WPF binding framework…

<TextBlock Text="{Binding CurrentSection.Gradient, StringFormat={}{0:0.0}%}" />…and if, for example, you have values being produced on a different thread, you can quite happily take these values as they appear and update the property…

gpxPoints.Replay(backgroundScheduler).Subscribe(x => CurrentPoint = x);The WPF framework will make sure we’re back on the right thread before updating the UI.

If, however, the WPF binding in the XAML was replaced with a ReactiveUI one in code then we do get the same issue in the WPF app as in the Android one.

There’s a simple fix - use the Rx ObserveOn method to make sure the items produced are observed on the correct thread…

gpxPoints.Replay(backgroundScheduler)

.ObserveOn(RxApp.MainThreadScheduler)

.Subscribe(x => CurrentPoint = x);But there’s a better way…a more ‘ReactiveUI-y’ way. Instead of just using a normal Rx subscription to update a view model property from an observable, we can use an ObservableAsPropertyHelper…

To do this, we give our class an ObservableAsPropertyHelper member instead of the property’s backing field…

private readonly ObservableAsPropertyHelper<GpxSection> currentSection;…and set the ObservableAsPropertyHelper with the return value from a call to ToProperty. (The lambda expression specifies which notification to raise when the value updates)…

currentSection = gpxPoints.Replay(backgroundScheduler)

.ToProperty(this, x => CurrentPoint = x);The property itself becomes a read-only property returning the Value from the ObservableAsPropertyHelper…

public GpxSection CurrentSection { get { return currentSection.Value; } }So the CurrentSection property will always return the latest value produced by the observable and the property changed notification will be raised whenever a new value is produced. And this time, because we’ve been a bit more explicit with what we’re trying to do, the ReactiveUI framework can help us out and take care of the dispatching for us so the UI updates happen on the correct thread. We didn’t need to specify the thread to observe on.

Binding to Commands

There’s just one last thing I should mention. You know in that very brief discussion of ReactiveUI bindings earlier I mentioned about the set of classes that know how to create a command binding to various objects and how the framework can choose the most appropriate one? Well, at the time I was working on this project, the Android versions of these classes hadn’t been implemented yet. So it was time to find out how to implement my own and register it with the framework…

This is done by implementing an ICreatesCommandBinding. If you look at one of the existing implementations you can see it’s done in as general way as possible using reflection to look for certain properties on the object (e.g., if an object has a Command property which returns an ICommand and a CommandParameter property then I know how to bind to it). Unfortunately, the Android controls aren’t as consistent with their naming, making it quite awkward to use such a general approach. I guess this is why the Android command binding classes are a bit behind. However, it’s pretty straight-forward to implement one for a specific control type. I only need one to bind a command to an Android.Widget.Button…

public class CreatesAndroidButtonCommandBinding : ICreatesCommandBinding

{

public int GetAffinityForObject(Type type, bool hasEventTarget)

{

return typeof(Button).IsAssignableFrom(type) ? 2 : 0;

}

public IDisposable BindCommandToObject(ICommand command, object target,

IObservable<object> commandParameter)

{

return BindCommandToObject<EventArgs>(command, target, commandParameter, "Click");

}

public IDisposable BindCommandToObject<TEventArgs>(ICommand command, object target,

IObservable<object> commandParameter, string eventName)

{

var button = (Button)target;

var disposables = new CompositeDisposable();

disposables.Add(Observable.FromEventPattern(button, eventName)

.Subscribe(_ => command.Execute(null)));

disposables.Add(Observable.FromEventPattern(command, "CanExecuteChanged")

.Subscribe(x =>

button.Enabled = command.CanExecute(null)));

return disposables;

}

}The GetAffinityForObject is used to determine the most appropriate binding creator. It’ll use the one that returns the highest value for a given type of object. The documentation says “when in doubt, return ‘2’ or ‘0’” so that’s what I did!

This is how I registered it…

var resolver = (IMutableDependencyResolver)RxApp.DependencyResolver;

resolver.Register(() => new CreatesAndroidButtonCommandBinding(),

typeof(ICreatesCommandBinding));So, if you find you’re getting exceptions like “Couldn’t find a command binder for…” then you may need to do something similar.

Summary

And there you have it…the Android application now works just like the WPF one (and shares most of the same code). All I really needed to do was…

- Learn how to use ReactiveUI bindings

- Implement an

ICreatesCommandBinding(which will probably be part of the default framework eventually) - Change the view model to use an

ObservableAsPropertyHelper(which I probably should’ve been using anyway)

The rest of the Android application is just the axml layout equivalent of the WPF window and some code in the MainActivity for browsing for a GPX file. Nice!

1. Of course, learning new tools and technologies brings plenty of benefits to my .NET work as well. (Spend some time playing around with a more dynamic or functional language, for example, and you'll find it can often help give a different viewpoint or approach while working on a problem in .NET!)

2. The idea is to be able to use it with an exercise bike or turbo trainer to make your workouts a bit more realistic by following an actual outdoor route. You'd just watch the display and adjust the trainer's resistance according the displayed gradient.

3. Using xsd code generation (The less code I have to write myself is only going to mean fewer bugs, right?)

comments powered by Disqus

About

I work as a Software Developer at Nonlinear Dynamics Limited, a developer of proteomics and metabolomics software.

My day job mainly involves developing Windows desktop applications with C# .NET.

My hobby/spare-time development tends to focus on playing around with some different technologies (which, at the minute seems to be web application development with JavaScript).

It’s this hobby/spare-time development that you’re most likely to read about here.

Ian Reah